Our special exhibition "... for intellectual use"

Artistic Positions from the Winkler Collection

October 31st 2024 until March 16th 2025

The Winkler Collection is among the trend-setting individual endowments in the history of the MAKK. Its special structure enables it to permanently present an exhibition concept unique in Europe: Under the title “Art + Design in Dialogue”, works of fine art encounter contemporaries from the field of international product design. The nucleus of the extraordinary collection is, however, free art. Prof. Richard G. Winkler already began collecting outstanding works of art in the 1970s. His special area of interest here was in paintings and objects that had a constructive-concrete artistic approach in common.

On the occasion of his 90th birthday, the MAKK is dedicating the exhibition “… for intellectual use” to the donor. It focuses on the heart of his collections together with rarely shown objects. The title thereby refers to the “Zürcher Konkrete Kunst“ (Zurich Concrete Art) exhibition of 1949, in the context of which the artist Max Bill explained the objective of this art direction. The goal was “to create objects for intellectual use”.

Although the quote refers to a particular art direction from the mid-20th century, it can also be applied to objects from earlier or subsequent currents. The perspective of the collector on the inner relationship of the art styles and his well-founded knowledge of art-historical contexts are made very clear here. A further characteristic, common to all of Winkler’s collecting fields, is the striving for completeness. Thus, for example, the four most well-known founding members of the Zurich Concretists are represented in the collection with prominent works: Max Bill, Camille Graeser, Richard Paul Lohse, Verena Loewensberg. From Richard Paul Lohse, who developed two fundamental pictorial systems, there are thus of course representatives from both genres – the exhibition reflects the collecting idea as a microcosm.

Russian avant garde: pure intellectual revolution versus “off to the factory”

Pioneering stylistic directions for the art of the 20th century developed in Russia in rapid succession in the period between 1905 and the end of the 1920s. In the Winkler Collection, the focus is on the two most influential but contradictory currents: Suprematism and Constructivism.

Kazimir Malevich founded Suprematism, which hoped to advance a “non-representational sensibility”. This was the highest goal (lat. supremus). An appropriate example is the composition “Study No. 17”, dated to the end of the 1920s, of an anonymous artist, which will be presented in the exhibition. This involves a so-called “magnetic Suprematism”, in which the pictorial elements appear to attract one another.

The antithesis to this is provided by artists in the circle around Alexander Rodchenko, a co-founder of Constructivism. The objective of this direction was an emphasis on the technical development of the time and the call for the purposiveness of art. The brothers Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg are among the most inventive protagonists of this style. Their space constructions, which are also represented in the exhibition with a work by Georgii Stenberg, should evoke bridges, elevators, cranes or architectural frameworks.

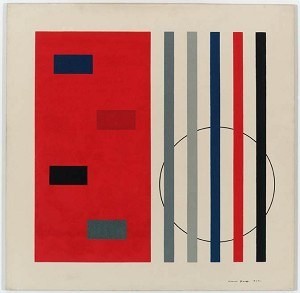

De Stijl – nucleus of abstract-geometric and constructive-concrete art

A small group of like-minded artists joined together in 1917 in Leiden in South Holland under the name “De Stijl” (= the style), among them the painter Piet Mondrian and the painter and art theoretician Theo van Doesburg. At the initiative of van Doesburg, the association also published a journal of the same name, which spread the ideas of the progressive artists until 1928.

The goal of the group was a new design, for which Mondrian in particular initially provided the theoretical foundation. He developed a purely geometric system with horizontal and vertical lines and restricted the colour scale to the primary colours as well as black, white and grey. Another important feature was the avoidance of symmetries. He also transferred this visual composition as “Neoplasticism” to architecture and objects.

Theo van Doesburg expanded on the system by, for example, incorporating the diagonal as a dynamic principle into his compositions. Unlike Mondrian, he traced his language of form back to mathematical-geometric principles as of the 1920s and coined the term “Concrete Art” in 1924.

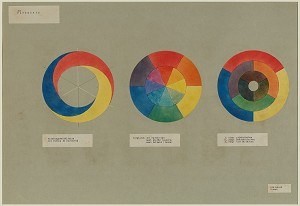

Bauhaus – universal ambition and stringent functionalism

The art institute founded in Weimar in 1919 aimed at a broadly based programme of training with intellectual-artistic and artisanal-technical aspects. While the focus was initially on the “unification of art and craftsmanship”, the intentions shifted through the “unity of art and technology” to the “definition of form through function and costs”. Especially the latter aspect would lead to a close affiliation with industrial production as a consequence.

Although industrial production of Bauhaus designs only took place in a few exceptional cases and sometimes at clearly later dates, the school developed into one of the most influential artistic institutes of the 20th century.

Although several students only studied a brief time at the Bauhaus, the creative impulses originating there are clearly recognisable in the paintings, advertising graphics and posters, colour studies or architectural photographs of the Winkler Collection.

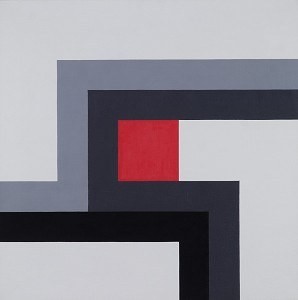

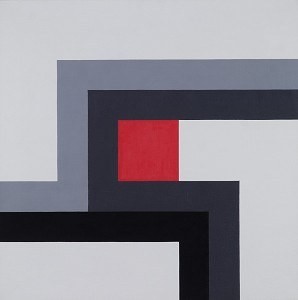

Concrete Art: colour and form as objects

In contrast with abstract art, in which colour and form are derived from visible objects, impressions of nature or living beings, artists of the “concrete” treat these pictorial elements themselves as objects. Colour and form are thus the realia of the works and cannot be traced back to anything outside of the composition, but also possess no symbolic character. Concrete Art should be visually comprehensible and be executed in an exact technique.

According to Theo van Doesburg, who coined the term, the influential artist, architect and designer Max Bill was one of the leading minds of the current. In the 1930s, he founded the “Zürcher Schule der Konkreten” (Zurich School of Concretists), of which Verena Loewensberg and Richard Paul Lohse were also members. The stylistic direction, which was especially prominent in Switzerland due to important exhibitions and publications, found proponents throughout Europe. The French artist François Morellet and the Swede Olle Bærtling are among its representatives.

ZERO: back to the start!

Heinz Mack and Otto Piene founded the “ZERO” artist group in Düsseldorf in 1958. They were joined by Günther Uecker in 1961. They particularly perceived the works of the prevailing Informal Art as too subjective and formless, the colour palette used as too mixed and dark. In the face of this, they wished to set the development of style back to “zero”, so to speak, in order to make a new artistic beginning possible. Central themes of their works were light, fire and movement, which they allowed to emerge in their works in diverse ways – with rotors that reflect light, silvery surfaces, brilliant colours, burn marks or nailed reliefs.

Although the group dissolved in 1966, their puristic ideas found an artistic echo, for example, in Almir Mavignier da Silva, Hermann Goepfert, Christian Megert or Adolf Luther. Works of these artists are also represented in the Winkler Collection. Ultimately, “ZERO” also provided impulses for contemporary and subsequent currents like Op(tical) Art or Light Kinetics.

Systemic Art – objective rules, astonishing results!

The influential Anglo-American art critic Lawrence Alloway, curator at the Guggenheim Museum in New York from 1961 to 1966, organised the “Systemic Painting” exhibition there in 1966 and coined the expression “Systemic Art” in the same year. Under this term, he understood constructive-geometric works that were structured according to comprehensible rules and in some cases with standardised forms.

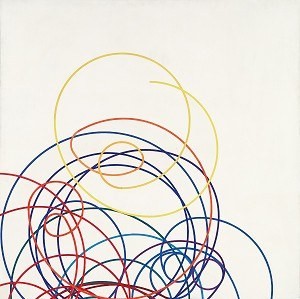

Artists of this direction worked, for example, with mathematical formulas or also according to principles of randomness, which were determined, for example, with dice or with the help of a computer. One of the earliest representatives was Zdeněk Sýkora, who already used the computer as an aid for his compositions in two successive series of works as of the early 1960s. For representatives of Systemic Art, the rational approach also often refers to series that are conditional for one another.

Funded by: